Wilhelmina Whales

During the 19 and 20th Century, humpback whales, along with many other whale species, were hunted almost to the point of extinction in Antarctic waters. However, with the cessation of commercial whaling in the 1980’s and protection of the Southern Ocean, these magnificent animals have made a strong recovery around many parts of the continent. As their numbers increase, their distribution, population and behaviour need to be studied to understand how they interact with the local ecosystem. In our changing world, this understanding can be applied to assess how ecosystem shifts stemming from climate change and fisheries, as well as impacts from increased tourism and shipping may impact these populations.

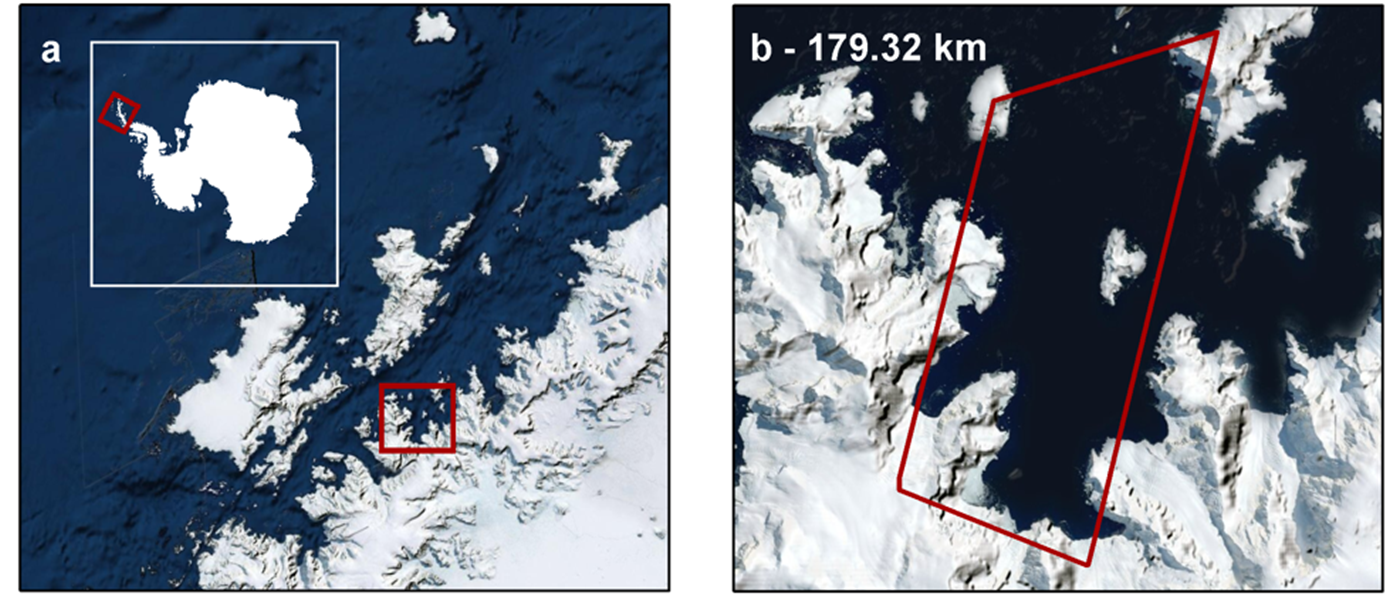

Monitoring whales is always a difficult task. They travel over huge distances and forage in remote areas. The most common monitoring platforms are ships, which in Antarctic waters often means an ice strengthened research vessel; always an expensive business. But, with the recent advance in satellite resolution, a team at British Antarctic Survey, part of the SOOS CAPS group, is monitoring whale populations on the West Antarctic Peninsula using very high-resolution imagery from the WorldView-3 satellite.

Humpbacks have an interesting niche in the Antarctic ecosystem. Unlike the large rorqual whales, such as blue and fin whales, which are mostly oceanic, humpback whales often come close to the ice edge and forage in the fjords and bays of the Antarctic Peninsula. Here they target rich aggregations of Antarctic krill that can be found there. Unlike the smaller minke whales, humpback whales do not go directly into the pack ice and so depend on areas that are fairly ice-free. As this region is warming rapidly, it has seen a reduction in sea ice extent and early loss of ice cover from the bays. Our hypothesis is that humpback whales increase in numbers in coastal bays over the course of their feeding season from November to March, as the sea ice retreats. We also think that many of them stay in Antarctic waters until the autumn months, and are using satellites to examine this.

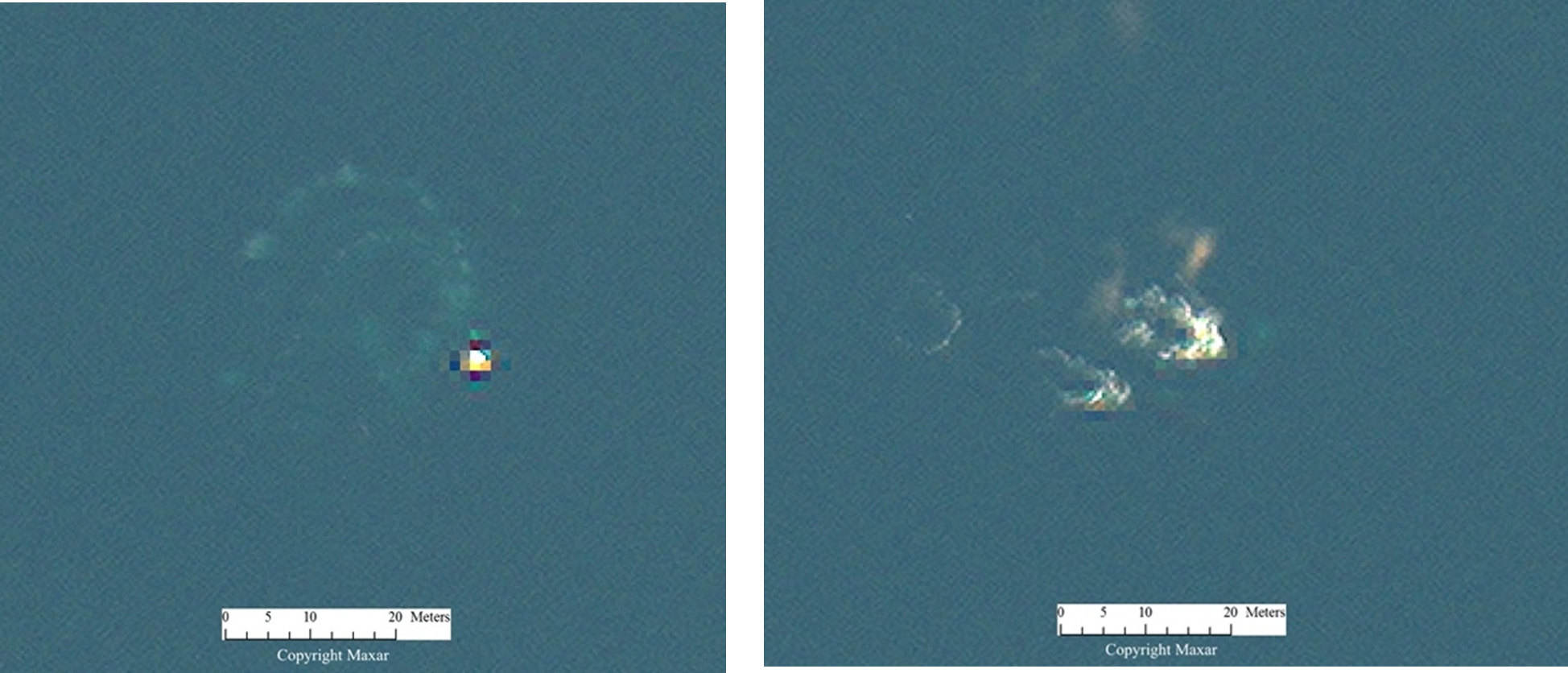

Our study area for this project is Wilhelmina Bay, an area that humpbacks are known to frequent in large numbers, late in the Autumn Season. We are tasking the satellite provider Maxar to collect multiple images from November to March of the whole of Wilhelmina Bay. We are also collecting duplicate imagery, taken a minute or two apart, to qualify our counts and assess availability bias – the percentage of whales that are visible on the surface at the time the image was taken.

Humpbacks are not always the easiest whales to see in satellite imagery. Although they are large and are often at the surface, they have dark bodies in a dark ocean and any splashes can be confused with ice or bash. Indeed, often the most visible signs of these whales are their blows, and the bubble nets and fluke prints that they leave behind when foraging. This makes it difficult to automate the process of finding them. Therefore, the project is getting multiple manual counters to assess each image to see not just what the average count is, but also how much variance we get in the imagery, which can be used as a metric of accuracy in itself.

The project should be finished by the summer and, building on work already done in the area, we hope to publish results soon afterwards.